Uranus and Neptune, and their Satellites

From Saturn, Voyager 2 moved onward, to pass Uranus and Neptune. As we noted before, both of these outer Giants are about 40% the diameter of Jupiter. Uranus and Neptune have densities of 1.28 and 1.63 g/cm3, respectively. Both have thick cores composed of rock mixed with water, ammonia, and methane ices, lack metallic hydrogen mantles, have thick gaseous envelopes (about 15% of the planet's mass) consisting of about 83% H, 15% He, 2% CH4 (methane) and traces of other gases. They also have rather faint, thin rings, and strong but distorted magnetic fields. Uranus has 15 known satellites, of which 5 are greater than 450 km (280 mi) in diameter. Neptune has 7, of which 2 are greater than 400 km (249 mi) wide. In this discussion, we describe only the larger ones.

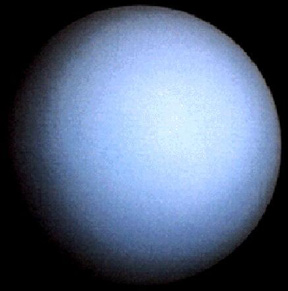

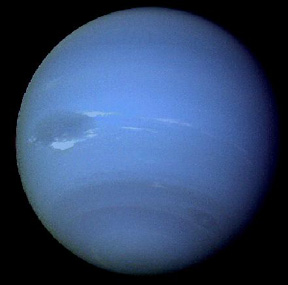

Seen in color by Voyager cameras, both planets appear similar, as shown here (Uranus on left; Neptune right):

Each has a notably bluish color, because methane gas absorbs longer wavelengths (reds and yellows) and reflects shorter wavelengths (blues). The atmospheres possess weak banding and Neptune displays a large Dark Spot and fast moving cloud spots that represent rising plumes and turbulence. Neptune's zonal winds can move as fast as 2,000 km/hr–the fastest measured, so far, in the solar system.

19-68:

Each planet has a few rings, which

are faint and thin. Uranus has 11 rings,

with the outermost (Epsilon) being much brighter than the others, as shown above. Two small satellites are visible on either side of the Epsilon ring. Scientists call these satellites, "shepherds," because they seem responsible for keeping that ring intact, by pushing stray particles back into line and possibly gathering and inserting particles from beyond. One of the rings around Neptune has a distinctive "braided" (twisted) structure:

The five outermost Uranian moons are also that planet's largest. They occur in the sequence: Miranda (472 km [293 mi] in diameter), Ariel (1,158 km [720 mi] in diameter), Umbriel (1,172 km [728 mi] in diameter), Titania (1,580 km [982 mi]in diameter), and Oberon (1,524 km [947 mi] in diameter). Oberon is the farthest from Uranus at 583,300 km (362,463 mi). Each has an icy surface, extending to unknown depths, making up about 40-50% of the volume but ending in a rocky interior.

The last four comprise a group, in which all show strong similarities, with their dominant features being craters (especially Umbriel and Oberon) and deep (some greater than 10 km [6.2 mi]), interconnected, gash-like valleys (particularly Titania and Ariel).

One hypothesis for the origin of these cracks contends that the satellites once had enough internal heat to melt the exteriors into liquid water, which induced tensional fracturing, when it later froze and expanded the ice.

19-69:

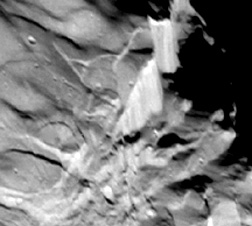

Miranda is unique among the Uranian satellites but, excepting its much smaller size, strongly resembles Ganymede in the Jovian group. By serendipity, Voyager 2 made the closest approach to Miranda of any of the satellites, so it could image the peculiar terrains in detail. Investigators based this flyby decision on the need to use this satellite to give the spacecraft a gravitational boost towards Neptune. First, look at the full view (top)¾ a mosaic¾ of one face. Then (below), view a close-up of the surface.

Two sharply contrasting terrains are evident. Much of Miranda's surface consists of rather bright, heavily cratered terrains, similar to the above four satellite exteriors. But there are three large oval-to-rectangular terrains (called coronae), whose physiographies are quite different (to each other and to the dominant terrain). They may contain subparallel grooves, several as deep as 2 km (1.2 mi), or alternating light-dark bands, or ridges and stripes that take sharp bends. A closer view (at bottom, above) of ridged terrain shows the generally abrupt boundaries of these terrains with the encompassing older terrain. Scientists still debate the origin of these patches. An early interpretation considered them to be fragments of a shattered proto-Miranda or some other disrupted satellite, incorporated in a (re-)assembling satellite. The paucity of craters in these isolated terrains argues against this. Another opinion holds them to be a mix of rock and ice that formed a crust, which broke up and was invaded by upwelled ice masses from the interior.

19-70:

Still another close view of the Mirandan surface shows high fault scarps and grabens in jumbled terrains.

Primary Author: Nicholas M.

Short, Sr. email: nmshort@epix.net

Contributor Information

Last Updated: September '99

Site Curator: Nannette Fekete